First, indulge me for a moment.

Towards the end of Alice’s Adventures of Wonderland, there is a court scene in which they are trying to prove who stole the tarts. The White Rabbit comes scurrying along carrying a piece of evidence: a letter. The King of Hearts asks him to read it aloud: “Begin at the beginning, and go on till you come to the end: then stop.”

This is what the letter says:

If you didn’t get that at all, you’re not alone. This is how everyone in the court reacts:

We have three kinds of responses here:

Alice: “I don’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it.”

Jury: ‘The jury all wrote down on their slates, “She doesn’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it,” but none of them attempted to explain the paper.’

King: “If there’s no meaning in it, that saves a world of trouble, you know, as we needn’t try to find any. And yet I don’t know…I seem to see some meaning in them, after all.”

How many Alices, juries and Kings of Hearts have we come across when confronted with the ‘point’ of an English degree? I have encountered many who don’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it, and many more who simply echo others who don’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it. Well-meaning relatives smile and admit that whilst they don’t get it, they are happy for me. Of course, it’s different for their own kids though. Their own kids ought to stick to maths and sciences and engineering etc.

I must say I side with the King of Hearts here. It is possibly the only time I will ever side with the King of Hearts — he is not the nicest of cards or kings. If there’s no meaning in an English degree, that saves a lot of trouble as we needn’t try to find any. Or fund any. And yet, I seem to see some meaning in it after all.

So after three years of studying English at supposedly one of the best places to study it, here are a few truths I have found to endure.

1. Do not expect any single institution to ‘teach’ you anything. The best ones do not teach — they unteach.

Oxford did not teach me anything. I never walked into a lecture and sat down and typed up notes about a set topic, within a set curriculum, to memorise within the set structure of a set exam. Unlike my friends in maths, who did that every week, or my friends in science, who did that every day. No one ever pointed to a whiteboard and told me that that quote or this fact was what I had to memorise to tick off a pre-ordained checklist of knowledge.

So what do English lectures do, if they do not teach anything? They unteach. One of the best lectures I went to was in my very first year. It was about metaphors. I walked in knowing exactly what a metaphor was: a literary technique where we apply a word or phrase to something which does not literally apply to that thing. The sun, for instance, cannot literally smile but it could metaphorically smile to imply that the weather was nice.

Then I walked into that lecture and a metaphor was no longer a metaphor. I realised that my ideas about what constituted a metaphor were incomplete because I had only ever considered a metaphor as something a writer sits down to write. And that’s because the only context in which I had encountered the word ‘metaphor’ was when studying what others wrote: hunting and highlighting ‘metaphors’ and ‘similes’ in poetry since GCSE.

But that lecture opened my eyes to metaphors in a much wider context: the context of language itself. We do not just write metaphors, like poets penning a particularly good line. No, we think in metaphor. And two guys figured it out years ago: George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, who wrote Metaphors We Live By to argue that many of our most fundamental ways of expressing ourselves revolve around metaphors, like HIGH = GOOD, LOW = BAD. Hence we say high-spirited to mean we feel good, and depressed, to mean not so good, or even just that we feel ‘high’ or ‘low’.

I was not taught what a ‘metaphor’ was. But I was untaught, and thus freed from, the limits of my own definition.

2. Critical thinking is a process of expansion, not filtration.

Even at Oxford, when we are asked to demonstrate ‘critical thinking’ in an essay, our instinct is to disagree. Disagree with the question and the questioner, the critic and the criticism. Disagree with everything we could possibly disagree with because that surely shows we are smarter. As I learned pretty quickly, it did not and does not.

The act of dissent is not wrong. There may indeed be something we disagree with someone about. What is concerning is that this has become our instinct; we are only listening to someone to disagree with them. That’s like picking up your child and scrutinising them all over for the smallest blemish.

We don’t even realise we are doing this, but here is what it can look like.

So what’s this critic said here? Ah, that they think ‘Sir Gawain and The Green Knight’ is an explicitly homoerotic poem. Ok well that’s just blatantly untrue. It’s implicitly homoerotic, not explicitly. There are no explicit scenes of homoeroticism. They’re just wrong. Ok noted, next?

This seems like critical thinking. After all, we’re not agreeing immediately with what someone is saying — we’re testing it against our own ideas before coming to the conclusion that that person is wrong.

It is, in fact, we who are wrong. This is not critical thinking; this is a process of filtration. We have constructed a barrier of ‘this is what I think’ and the point of view we are presented with either passes (agrees with what we think) or fails (disagrees with what we think) in which case we disagree with it too. There is a rather glaring flaw with this, which is that this only ever reinforces what we already think.

Real critical thinking looks something like this.

So what’s this critic said here? Ah, that they think ‘Sir Gawain and The Green Knight’ is explicitly homoerotic. Hmm, is it? Why do they think so? Well, it seems that they think so because there are multiple scenes in which Lord Bertilak and Gawain exchange kisses. That’s actually more explicit than I thought. I guess it could be explicitly homoerotic. But this remains largely implied because nowhere does Gawain or the Lord suddenly say “I love you”. Ok noted: ‘Gawain’ is a text that is more explicitly homoerotic than I thought, although I still wouldn’t call it ‘explicitly homoerotic’ overall. Next?

Critical thinking is not a process of filtration but a process of expansion; you grow to become a person who learns, tests and plays with a new idea, rather than disengaging with it right away because they do not seem to fit your pre-made moulds for thinking.

3. To grow most deeply, we must feed our curiosity. And to feed our curiosity, we need freedom and feedback.

Having volunteered for every ‘open day’ my college hosts — Oxford being a ‘university’ made up of decentralised ‘colleges’ — one question comes up again and again from the forty-or-so 17-year-olds sitting in front of me: “What’s the best thing about Oxford?” Or sometimes, a variation: “What makes Oxford Oxford?”

I can tell you what does not make Oxford ‘Oxford’. It is not the fancy ‘formals’ (semi-regular occasions where we dress up and have dinner in a fancy hall). It is not the prestige or the branding, as effective as it is. It is not even the world-class researchers, though there are many.

It is, quite simply, the freedom and feedback to feed our curiosity in order to grow most deeply. To understand what I mean by this, I will first unveil to you a realistic snapshot of a week during my term time at Oxford.

Monday: I am given a prompt either in class or by email. We will have been studying a period, for instance, 1660 to 1760. The prompt is usually one or two key topics of the period, for instance satire in the 18th century. I am given some suggested starting points, usually a mix of authors and texts: Jonathan Swift (‘A Modest Proposal’), Alexander Pope (‘The Rape of the Lock’), John Gay (‘Trivia’), Voltaire (‘Candide’)…

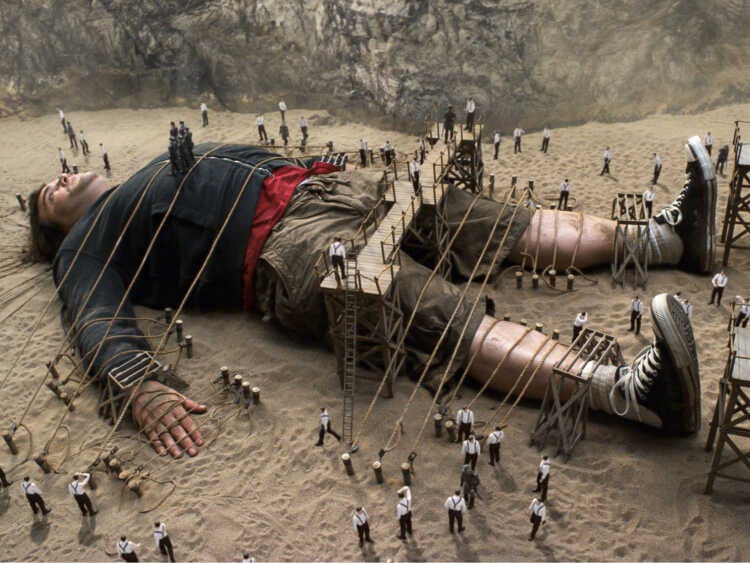

Tuesday: I take a look at the reading list and see what I find interesting. I look up Jonathan Swift on Wikipedia and realise, to my delight, that he wrote Gulliver’s Travels. I remember watching the film version starring Jack Black and finding it hilarious. I decide to write about Gulliver’s Travels.

Wednesday: I read Gulliver’s Travels. Many cups of tea are consumed.

Thursday: I continue reading Gulliver’s Travels. I start making the occasional note of things that are weird. Like the talking horses who casually debate genocide.

Friday: I finish reading Gulliver’s Travels. I now have collated a list of things I found weird and/or interesting. I look at my list and note down any connections or underlying themes behind the questions. I notice one thing that seems to connect them is the way we are told the story: through Lemuel Gulliver himself. Who even is Lemuel Gulliver? Is he supposed to stand in for Swift? But the things he says and does sometimes are so silly, like how he can’t stand being near his wife after being converted to whatever cult those talking horses were part of. Thus, I arrive at a more fundamental question of: how does the narrator destabilise the targets of satire?

Saturday: I begin forming my argument from first principles. They look something like this.

Satire works through analogy.

Analogy is when we compare A to B in order to understand certain properties of A better because we understand certain properties of B.

Satire works the same way but by attacking A through attacking B.

But what happens when we introduce the variable of a narrator? Especially an opinionated and unreliable one like Gulliver?”

I read up on this to see what answers other people offer, such as Nicholas Diehl’s ‘Satire, Analogy, and Moral Philosophy’. I see and make notes on where I agree and where I disagree — and, crucially, how my thoughts change after reading him. I do this with one or two more texts, after checking to see who Nicholas Diehl had read and referenced: Robert Quintero, Noel Carroll…

Sunday: I write this up into an essay about how having an unreliable narrator disrupts the fundamental structure of satire, which depends on analogy between a fictional world/character and a real-life target, and use Gulliver’s Travels as a case study. I submit it.

Monday: I have a 30-45 minute tutorial, which is a one-to-one conversation with my tutor, a professor specialising in the period I am studying in. We discuss my essay in depth. They push my thoughts, including my fundamental premises: can satire be founded upon by anything other than analogy? Why do I think Swift deliberately created the character of Lemuel Gulliver to tell the story of Gulliver’s Travels? Why did he, after creating this fictional narrator, then pretend it was real by publishing it under Lemuel’s name and not his own? How does Gulliver’s Travels change our understanding of the genre of satire?

By the end of that week, I have grown into someone who has considered deeply the nature of satire and, by analogy, the nature of analogy. And this has only been possible because I have had

a) the freedom and time to read whatever I want, and

b) the feedback to push my thinking further.

This, then, is the real value of an institution like Oxford: it gave me time to think slower, space to think deeper, and precious personalised feedback to think harder. All three variables are indeed possible without Oxford — and I would encourage them in any context — but I understand all too well how much harder they are to come by when we are caught up in lives that demand so much of our time, space and thought. Which brings me to my final point…

4. We need literature.

Books can’t pay our taxes, or our bills. Books won’t keep us well-fed or well-slept. Books won’t even make us better people by default.

But you know what books can do? They can give us words. And if you think I’m being cliche, just take a look at the etymology of ‘give’:

Books bestow words upon us; they deliver words to us; they allot words; they grant us words; they commit us to words; they devote words to us; they entrust us with words.

Books give us words. Suddenly that word has a lot more weight.

It is a weight I did not understand until life pressed it upon me again and again. The first time was when I was in my first year of university. I had just been told my grandmother, who had raised me from an infant till I was four, had leukemia. My first-year exams were weeks away. I was a mess. Then, for some strange reason, I came upon Thomas Brown’s Hydriotaphia, or Urn Burial. He had written it in 1658, and this is what he had to say.

Life is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible sun within us.

I cannot tell you how many times I returned to that phrase and its implications: that I was consumed by the very life that sustained me; that we all carried suns within us; that we walk among those who are on fire, yet only really touch the surface and never the blaze; that someday we will flicker, dim and vanish; that even when the body is gone, the trace of that hidden sun remains in the hands we touched, the bodies we warmed, the minds we loved; that I carried the suns of those I loved within as much as they carried mine; that to love someone and watch them fade is to fold their fire into ours.

Thomas Brown was not on any reading list I had, nor any revision schedule. In fact, I do not even remember how I came across him. The only reason I picked up Hydriotaphia, or Urn Burial was because I thought ‘Hydriotaphia’ was a weird word. Yet by following that simple act of instinctive curiosity, I allowed literature to find me instead. This odd prose-poetry-treatise on water burials ended up giving me the words I needed to hold on, at least long enough to get through preliminary exams.

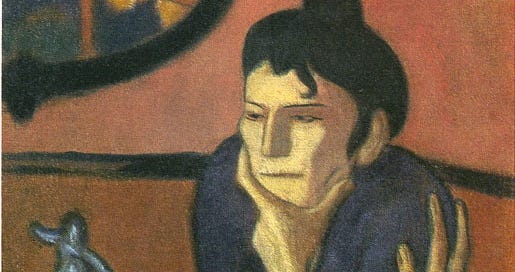

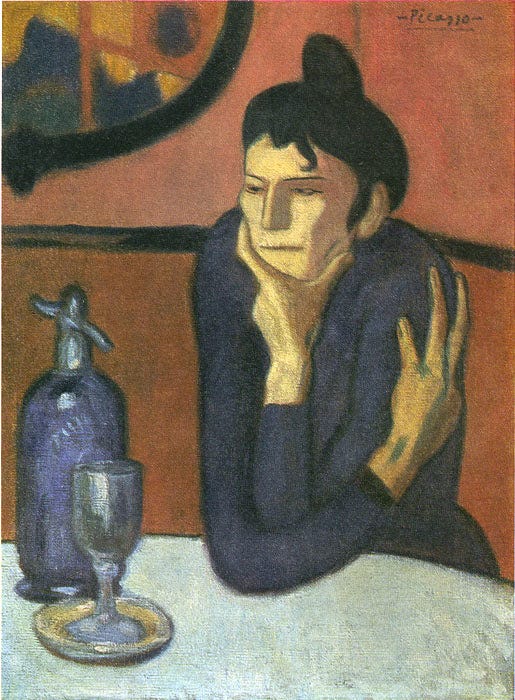

The second time was when I realised, halfway through my degree, that there were people in my life that I needed to let go of. Specifically, friends, or people I had considered friends. I found being with them draining, yet time and shared experiences had bound us to this indefinite contract of sustained interaction. I had wondered then if perhaps it was my problem, that I should hold back on talking about the things that made me happy, whether it was small recent achievements, or obsessive and disparate interests. It certainly did not seem to make them happy. In fact, I had begun to question the notion of ‘happiness’ at all.

What even was happiness? I decided to look it up on Poetry Foundation and clicked on a random search result: a poem by Raymond Carver.

I read that. I read it again. And then I started crying, and once I had started crying, I could not stop, which was retrospectively cathartic but at the time seemed pathetic. This, I remember thinking distinctly, was what happiness was.

Months later, I had let go of that friend.

The third time literature found me was towards the end of my final year. I was job-hunting and had accumulated close to fifty applications rejections: applications that I had spent days researching for; applications that I had proceeded to final rounds for; applications that had me bending my reason for existence to fit the company’s reason for existence. I was sick of pep talks that told me it’s not about how hard you can hit, but how hard you can get hit, or self-help books sermonising on how suffering was the prerequisite for success and that all I needed was sheer force of will to push through failures.

I didn’t want self-help books. I wanted soul-help literature. Once again, it found me when I could not find it. This time, through Mary Oliver in her poem, ‘When Death Comes’.

When death comes like the hungry bear in autumn; when death comes and takes all the bright coins from his purse to buy me, and snaps the purse shut; when death comes like the measle-pox; when death comes like an iceberg between the shoulder blades, I want to step through the door full of curiosity, wondering: what is it going to be like, that cottage of darkness? And therefore I look upon everything as a brotherhood and a sisterhood, and I look upon time as no more than an idea, and I consider eternity as another possibility, and I think of each life as a flower, as common as a field daisy, and as singular, and each name a comfortable music in the mouth, tending, as all music does, toward silence, and each body a lion of courage, and something precious to the earth. When it's over, I want to say: all my life I was a bride married to amazement. I was the bridegroom, taking the world into my arms. When it's over, I don't want to wonder if I have made of my life something particular, and real. I don't want to find myself sighing and frightened, or full of argument. I don't want to end up simply having visited this world.

Mary Oliver did not solve my unemployment. Nor did she give me the motivation to ‘push through’ applications. Rather, she gave words to the questions I had not dared to ask myself, let alone answer. If I ‘look upon time as no more than an idea’, if I ‘consider eternity as a possibility’, if I ‘don’t want to end up simply having visited this world’, what then?

I still don’t have the answer. But now I have the words for the question.

5. All of which is to say…

There is a point to studying literature, but the bigger point lies in living literature. To take the words that we are given and think through them, play with them, seek solace from them, and ultimately test them out in life.

After all, literature is for living because it is for the living.

Love,

Your friend from afar.

Sometimes getting a degree in the humanities seems like being able to see magic in the world, and spending years of your life studying that magic - the history of it, how to make it, trying to make it yourself - then going out into the world with people who don’t believe that magic’ even exists, even if you hold it up to them. There are people who simply deny it, and others who try to understand it, but due to misunderstanding or trying too hard, miss it. I feel like I’ve seen so many people respond to my exuberance over literature and philosophy like a wooden fish, the ones that Buddhist monks tap repeatedly with a stick, mouths slightly ajar. But some days, one of the best feelings is making a nonbeliever see for the first time. Saying something, reading something, sharing something that came at the right time in the right way to them, because some formulations words are able to enter the ear better than others, and when one works particularly well, everyone can see the magic.

Chenrui, your writing helps people see the magic. I always get so excited when you update.

this was an amazing read and incredibly validating as another english degree student, thank you! what surprised me most was that you wrote the whole tutorial paper in a day haha